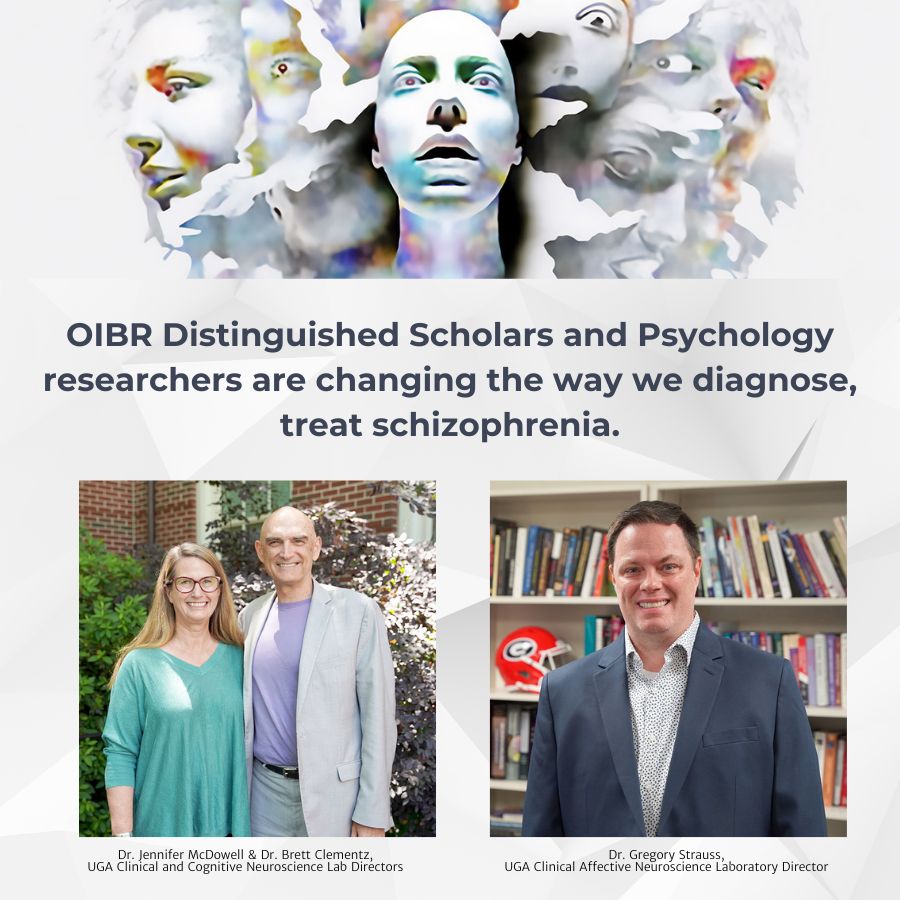

Asking better questions: Psychology researchers changing the way we diagnose, treat schizophrenia

OIBR distinguished scholar, Brett Clementz doesn’t love the term “schizophrenia.”

Sure, a quick glance down his extensive publication history might yield several uses of the word, but the University of Georgia Distinguished Research Professor finds it obsolete and imprecise.

It doesn’t capture the nature of the illness, he said, which is much more complex than society’s common definition.

The popular understanding goes something like this: An individual, usually a young adult, begins having hallucinations—“hearing voices” is a common description. Believing these misperceptions to be genuine, they lose their grip on reality and withdraw from family and friends. Taken to their conclusion, the symptoms may result in unpredictable and dangerous behavior.

That’s the popular belief. But it’s not entirely accurate.

In reality, there are far more factors that go into determining an individual’s unique neurological disorder. Different behavioral symptoms call for varying responses. Social support systems, which can impact escalation of the condition, are diverse. On top of it all, everyone has their own genetic and neurological makeup, meaning not all diagnoses—nor treatments—are equal.

Therein lies the problem with traditional approaches to schizophrenia. Diagnoses can lack specificity, making it difficult to tailor effective treatments. Additionally, while 10-15% of the adult population has experiences associated with schizophrenia, only a small portion develops more pronounced, diagnosable symptoms.

So, what makes one high-risk individual capable of living a perfectly unencumbered existence, while others are left struggling? That’s what a pair of research groups at UGA are trying to understand.

From investigating early symptom onset to distinguishing people’s various unique neurological conditions, the researchers are hoping that a better understanding of schizophrenia and similar disorders can lead to more precise diagnoses, better treatment and an overall clearer perception of the disorder.

A new lens for psychosis treatment

Schizophrenia is one of the main psychotic mental disorders outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the standard for diagnosis in clinical psychology. Psychotic bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder, also commonly diagnosed, share similar symptoms.

In the text, schizophrenia is marked by delusions or hallucinations, a departure from early definitions that centered on affect (or emotion), perception of self and volition. Bipolar disorder, meanwhile, focuses more on the mood, characterized by episodes of depression and mania. And schizoaffective disorder, like the center of a Venn diagram, displays a bit of both. Clinicians must distinguish between the three based on their own observational analysis and patients’ limited self-reports.

Beginning to see the problem?

While the DSM is the standard, its definitions of psychotic subtypes and the methods with which they are diagnosed is enough to draw skepticism from many experts.

In 2010, Clementz began working with the Bipolar, Schizophrenia Network for Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP), a consortium backed by more than $20 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health to fill in the gaps. Originally, they examined brain activity and structure to find biomarkers that more clearly defined the psychotic disorders outlined in the DSM.

Some small-scale studies identified occasional shared physiology between individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and their clinically normal first-degree relatives, but results from other groups greatly differed.

After finding no pattern, they took a different approach.

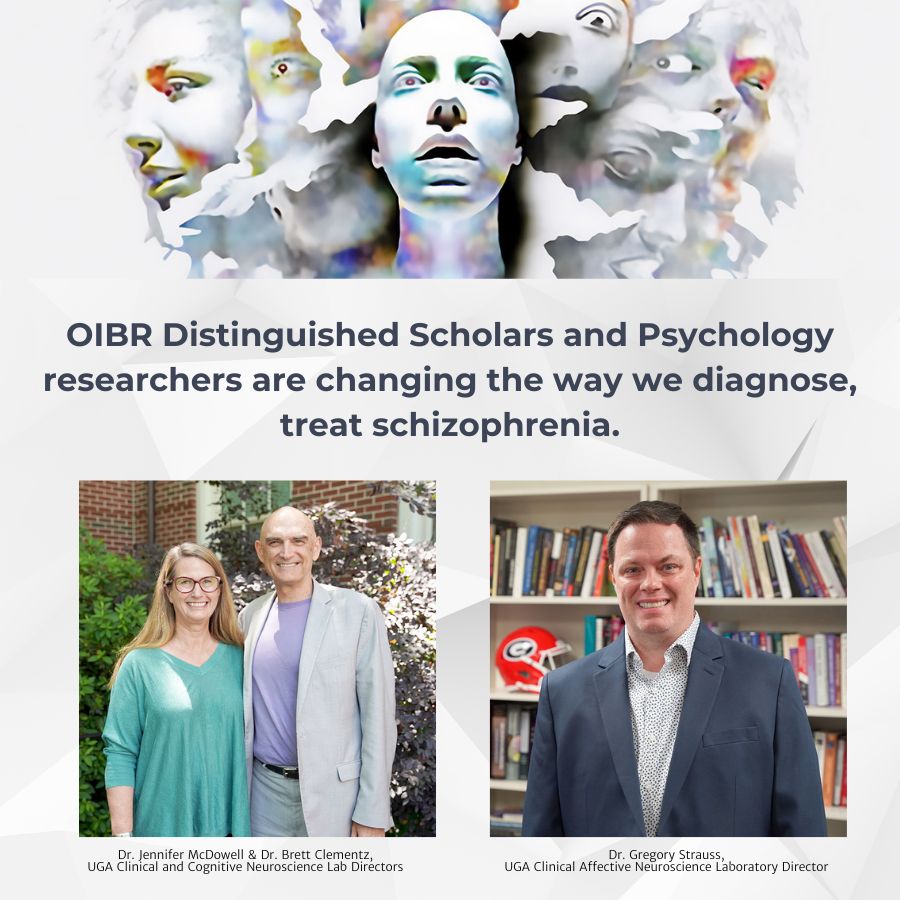

“We had been playing around with other ways of looking at the data,” said Clementz, who co-directs the Clinical and Cognitive Neuroscience Lab with OIBR Associate Director and Professor Jennifer McDowell. “There are statistical approaches called ‘numerical taxonomy.’ Instead of assuming you know the groups—like schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and psychotic bipolar disorder—you throw that out the window and look for statistical patterns that might indicate new groups.”

Numerical taxonomy uses statistical values derived from tests like electroencephalography (EEG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ocular motor measures and more. Researchers will perform tests that measure a subject’s cognitive control.

“There are two ways your brain works,” Clementz said. “The first is that you have a background level of wow and flutter, which everyone has. Your brain is always doing something. Then, if we present you with a stimulus, your brain will respond to that in some way.”

Measurements of these responses form the foundation of the numerical taxonomy. Clementz, McDowell and their teams reviewed data and compared it to data gathered for clinically normal first-degree relatives.

Finally, a pattern emerged.

“We saw the same patterns in the relatives that we did in the patients,” Clementz said.

It indicated a physiological liability inherited from a parent and offered a more precise option to categorize everyone’s unique psychotic experience.

They’re called biotypes. Like the DSM, they are divided into three classifications. Instead of being based on blanket behavioral thresholds, however, they are tailored to the individual. The main clinical characteristics differentiating the biotypes are thought disturbances, lack of spontaneous speech and low involvement in social and occupational activities.

Biotype-1 cases have low neural response to stimuli and poor cognition. Biotype-2 display poor cognition but also overactive neural responses and poor sensory motor inhibition. Biotype-3 was nearly normal on all biomarkers. All three included individuals from each of the DSM’s three psychotic diagnoses.

“In Biotype-1, we see low levels of background wow and flutter, and their ability to respond to a stimulus in the environment is low,” Clementz said. “So, that signal-to-noise ratio, which you need to function in society, is very bad. In Biotype-2, though, we see an equally bad signal-to-noise ratio, but it’s there for an entirely different reason. Their background wow and flutter is so high, they still have a hard time differentiating that stimulus from the background.

“These people are a mix of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar cases. In the typical approach of the DSM, both subgroups are treated the same, and that makes no sense.”

Researchers are currently studying how this new approach to psychosis can impact treatment. One study will see how repurposing an antipsychotic drug called Clozapine can affect treatment outcomes for one of the biotypes.

“Based on the literature, we think only one particular biotype should benefit from that,” Clementz said. “But you couldn’t tell that from the DSM diagnoses because they were spread across all three of our biotypes. The biotypes are transdiagnostic.”

Clementz cautioned against considering this an answer to a long-held diagnostic problem. They’ll explore how treatments affect each and continue to tease out data within the biotypes, which may result in additional classifications.

“We haven’t necessarily made any conclusions yet,” said McDowell, professor in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences’ Department of Psychology and associate director of the Owens Institute for Behavioral Research. “But science isn’t just about providing answers, it’s also about asking better questions.”

Another group on campus is asking new questions about a different stage of the schizophrenia experience.

Identifying risk before it takes root

In the Clinical Affective Neuroscience (CAN) Laboratory, researchers are taking a novel approach to early identification and prevention of schizophrenia, as opposed to treating those who have already received diagnosis.

OIBR distinguished scholar, Greg Strauss, who leads the lab, was an undergraduate student at UGA when he had his first encounter with this research focus.

“I was captivated by the notion of preventing psychosis,” said Strauss, a professor in the Department of Psychology. “I went off to grad school and postdoctoral research studying people who were in the chronic phase. At that point, many don’t recover.”

To make a difference, he considered, may require studying the early-stage “prodromal” period of the disorder—before attenuated hallucinations or delusions ever emerge.

About 10-15% of the world’s population has sub-threshold psychotic experiences. Sometimes those entail hallucinations or delusions that don’t cause distress or interfere with functioning. Other times, though, they do interfere with functioning. Called “attenuated psychosis syndrome,” it’s a relatively smaller portion of the population.

“So, a large portion of society has some unusual thoughts or perceptions, but there’s something that allows them to be resilient and not develop the disorder,” Strauss said. “Some also have problems with motivation, initiating social activity, feeling or expressing emotion, and we think the constellation of all those things puts people at greater risk.”

The current standard is to assess symptoms and give people a label of “clinical high risk.” Patients will sit for a standard interview about their symptoms.

“We try to phrase questions in a way that is open or not labeling to increase their willingness to share,” said Lauren Luther, a research scientist in the CAN Lab. “But it is largely reliant on self-report.”

That’s a problem. Individuals are biased when it comes to personal experience. There is also significant stigma surrounding mental disorders, and patients may not admit that anything is wrong, much less accept help. Researchers seek collateral information—from a clinician or family member, for example—but sometimes it’s not possible to gain a clear understanding.

Another problem, specificity, looms arguably larger.

“We say these 10-15% are at high risk, but only 20% in that group go on to develop psychosis,” Strauss said. “So, our measures have poor specificity in predicting who is going to develop it or not.”

The CAN Lab, which is conducting several studies funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), is offering several new approaches to address these shortcomings.

One is a 50-site worldwide study that is the largest of its kind conducted by the NIMH. Backed by about $100 million in funding, it is part of the Accelerating Medical Partnership in Schizophrenia’s Psychosis Risk Outcomes Network (ProNET) initiative. UGA and 25 other U.S. institutions are studying a variety of biomarkers—brain scans, blood tests, genetic data and more—to better predict outcomes of high-risk individuals.

Another is called “digital phenotyping” and takes advantage of modern technologies to gain a more consistent and clearer picture of the individual. Cell phones and smart bands follow their owners around all day, providing opportunities for researchers and clinicians to engage with patients or monitor daily activities.

Patients receive prompts throughout the day to immediately complete a survey: Where are they? Who are they with? How are they emotionally, and what symptoms are they having? The surveys allow them to answer more clearly and honestly without their recollection being clouded by time.

But there are also tools like accelerometry that can measure how much they are moving and geolocation to see whether they are spending all their time isolated at home or with friends or family. The microphone can measure how much speech is happening in the background, and researchers can also have them record a video to be analyzed by software that can interpret emotion in the face and voice.

A 2022 study validated the use of accelerometry in digital phenotyping, demonstrating correlations with active self-reports of time spent in goal-directed activities and motivational symptoms. Another study in 2021 showed that machine-learning algorithms with access to geolocation and accelerometry data could classify the presence of a psychotic disorder with 80% accuracy.

“We think that by measuring these behaviors in the real world, we might be able to obtain better sensitivity and specificity in predicting psychosis than clinical interviews alone,” Strauss said. “In particular, we’re interested in negative symptoms like reduction in motivation, socialization or emotion. These occur years before subthreshold hallucinations or delusions and offer the earliest window into the risk period.”

A remaining key barrier to early detection is access—to care (for patients) and to the patients themselves (for clinicians). Only about 20 sites in the United States (one of which is at UGA) and fewer than 100 in the entire world are specialized in performing clinical evaluations for psychosis risk.

Strauss offers a couple of potential solutions.

One is a six-site study called Computerized Assessment of Psychosis Risk. Funded by about $10 million from NIMH, it is developing a computerized battery of tests meant to tap into the neural mechanisms underlying symptoms. These tests will be administered online to predict an individual’s level of developing a psychotic disorder. Developing a tool that clinicians without specialized training can use to determine psychosis risk may allow more individuals to receive services who would have never otherwise been referred for help.

Another is simply to reduce the stigma.

“I’ve often wished that something like the ALS ice bucket challenge would be done for serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia,” Strauss said. “We need to raise awareness and try to understand the disorder before it takes root.”

Original story: Written by David Mitchell

Photo of Dr. McDowell & Dr. Clemenz: Lauren Corcino

Photo of Dr. Strauss: David Mitchell